Contents

Thursday, August 28, 2025

On August 7, 2025, the Supreme Court of British Columbia released its precedent-setting decision in Cowichan Tribes v. Canada (Attorney General), 2025 BCSC 1490 (“Cowichan”).[1] The case is a huge victory for Cowichan Tribes and sets an important precedent for First Nations and Crown governments across the country. The court in Cowichan found that Aboriginal title exists on lands held in fee simple, and issued a declaration to that effect – a first for any court in Canada.[2] And, the court has ruled that some of those fee simple lands should be returned to the Cowichan Tribe’s ownership and control, another first and a significant milestone in the law around Aboriginal title. In doing so, the court clarified several important principles about how Aboriginal title and fee simple can interact with each other, and definitively rejected arguments that fee simple title can somehow displace or overtake Aboriginal title.

While this decision is a significant victory, the 513-day trial also raises real questions about access to justice, and the enormous burden the Canadian legal system places on First Nations if they want to protect their constitutionally protected rights to their territory and get real remedies for the Crown unlawfully giving away First Nations land.

BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY OF DECISION

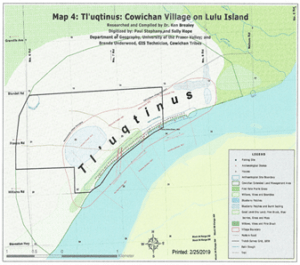

In this case, Cowichan Tribes claimed Aboriginal title to their traditional village of Tl’uqtinus, surrounding lands, and lands under water near the village. The claim area covered approximately 1846 acres of land, and is located within what is now known as Richmond, British Columbia. All of the claimed lands are presently owned by the federal Crown, the City of Richmond (“Richmond”), the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, and private parties that weren’t named or involved in the litigation. Cowichan Tribes also sought a declaration that they have an Aboriginal right to fish for food in the south arm of the Fraser River.

The Cowichan Title Lands are outlined in black in the above map.

The court recognized Cowichan Tribes’ Aboriginal title to a portion of the claim area, including a strip of submerged lands in front of the traditional village site and fee simple lands owned by Canada and Richmond (the “Cowichan Title Lands”). The court also found Cowichan Tribes established an Aboriginal right to fish for food. The court further found that:

- The fee simple grants issued in the Cowichan Title Lands area were largely made without constitutional or statutory authority. This is because the reigning policy at the time was to exclude Indigenous lands from sale to settlers.

- The fee simple grants were unjustified infringements on Cowichan Tribes’ Aboriginal title.

- None of the defendants’ defences, including reliance on the Land Title Act’s guarantee of indefeasibility of registered title, limitations, laches, or bona-fide purchaser for value without notice, were successful.

Given these findings, the court issued the following declarations:

- The Cowichan have Aboriginal title to the Cowichan Title Lands;

- The Crown grants of fee simple interest and the presence of certain highways in the Cowichan Title Lands unjustifiably infringe the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title;

- With a small exception,[3] Canada and Richmond’s fee simple titles and interests in the Cowichan Title Lands are defective and invalid;

- With respect to the fee simple lands owned by Canada that have not been declared invalid, Canada owes a duty to the Cowichan to negotiate in good faith the reconciliation of the fee simple with Cowichan Aboriginal title, in a manner consistent with the honour of the Crown;

- With respect to the fee simple land held by people who are not parties to the litigation (unlike Canada and Richmond, who were defendants), BC must negotiate with Cowichan in good faith to reconcile the grants of fee simple interests with Cowichan’s Aboriginal title, in a manner consistent with the honour of the Crown; and

- The Cowichan have an Aboriginal right to fish the south arm of the Fraser River for food within the meaning of s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.

WHAT HAPPENS NOW

The Cowichan have Aboriginal title to the Cowichan Title Lands, and “[h]ow the Cowichan share and exercise the rights recognized in this proceeding is completely up to them”.[4] It is worth emphasizing once more that all of this land is currently held in fee simple by Canada, Richmond, and other third parties who were not defendants at trial.

For the land owned by Canada and Richmond, with the one small exception noted above, the fee simple titles have been declared invalid and defective. That means that this land will be returned to the Cowichan. The parcels owned by Canada are largely industrial lands, and the parcels held by Richmond are mostly undeveloped and unoccupied. The declaration of invalidity of these fee simple titles has been suspended for 18 months “to allow for an orderly transition” and give the Cowichan, Canada, and Richmond “the opportunity to make the necessary arrangements” for the transfer of land.[5]

For the lands held by third parties who were not defendants to the claim, the fee simple titles “are valid until such a time as a court may determine otherwise or until the conflicting interests are … resolved through negotiation.”[6] As mentioned above, BC has an obligation to negotiate with Cowichan in accordance with the honour of the Crown to resolve these conflicting interests. For now, the Cowichan’s exercise of their Aboriginal title is “constrained by the existing fee simple interests to the extent it is incompatible with the fee simple interests.”[7] These fee simple interests may be “challenged in subsequent litigation, purchased, or remain on the Cowichan Title Lands.”[8] Should the Cowichan pursue subsequent litigation, the private landowners will have the opportunity to be heard and avail themselves of any defences (including that they were not given formal notice of the proceedings).[9] But that is not a matter for the court to address now. The court agreed with the judgment in Wolastoqey Nations v. New Brunswick and Canada, et al that the conflict between Aboriginal title and third party fee simple interests will first fall to the Crown to negotiate and reconcile in accordance with recent Supreme Court of Canada guidance.[10] The court stated that “BC and the Cowichan should be afforded space to reconcile these competing interests. It is an issue for the Crown and not the private landowners to resolve.”[11]

Although the court does not address the possible outcomes of negotiations between BC and the Cowichan, some potential avenues could involve BC: compensating the Cowichan for the unjustified infringement of the presence of fee simple title on its Aboriginal title land; purchasing the land (or some parcels of it) and returning it to the Cowichan; expropriating the land (or some of it) to return it to the Cowichan; and/or acknowledging the jurisdiction of the Cowichan over the land (with the caveat that the courts have so far been hesitant to acknowledge or explore the jurisdictional elements of Aboriginal title).

KEY RULINGS

1. Provinces do not have jurisdiction to extinguish Aboriginal title

More than 25 years ago, the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw ruled that provinces do not have jurisdiction to extinguish Aboriginal title. In order extinguish Aboriginal title, legislation needs to reflect Crown’s clear and plain intent to do so. However, any provincial legislation with the requisite clear and plain intent to extinguish would be a law in relation to “Indians and Indian lands” which is under the federal government’s exclusive jurisdiction. So “a provincial law could never…extinguish aboriginal rights, because the intention to do so would take the law outside provincial jurisdiction”.[12]

Richmond argued that this law was overtaken in Tsilhqot’in. In that case, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that interjurisdictional immunity was not the appropriate framework for assessing whether a province’s interference with an Aboriginal right is constitutional. Rather, the justified infringement framework should apply. Richmond suggested this logic should be extended to extinguishment.

The court in Cowichan disagreed. It found that in Tsilhqot’in, the Supreme Court of Canada only did away with the doctrine of interjurisdictional immunity “to the extent it has been overtaken by the infringement/justification framework under s. 35”.[13] The prospect of extinguishment arises before the enactment of section 35 (and by implication, prior to the protection of the justified infringement test). As such, “in assessing provincial regulation of Aboriginal title lands prior to the enactment of s. 35, there is still a role for interjurisdictional immunity.”[14] This means that provinces were never able to extinguish Aboriginal title.[15]

This is important confirmation that only the federal government had jurisdiction prior to 1982 to extinguish Aboriginal title. Defendants to Aboriginal title claims thus cannot rely on provincial actions (such as provincial land legislation) to prove extinguishment.

2. Fee simple grants do not “displace” or otherwise automatically trump Aboriginal title

At trial, Richmond argued that fee simple and Aboriginal title are fundamentally incompatible and simply cannot coexist, and that thus fee simple ‘displaced’ Aboriginal title such that it no longer exists where fee simple is granted. The court categorically rejected this theory, ruling that displacement is “without foundation in Canadian law and is, in essence, a form of extinguishment” (but one that does not actually meet the strict requirements of extinguishment).[16]

In rejecting displacement, the court highlighted several key principles about the unique and constitutional nature of Aboriginal title, stating that:

- “Aboriginal title is not inferior to other rights and interests in land. Uncertainty should not cause courts to prioritize fee simple interests over Aboriginal title.”[17]

- “Aboriginal title is a prior and senior right to land. It is not an estate granted by the Crown, but rooted in prior occupation. It is constitutionally protected. The question of what remains of Aboriginal title after the granting of fee simple title to the same lands should be reversed. The proper question is: what remains of fee simple title after Aboriginal title is recognized in the same lands?”[18]

- Aboriginal title crystallized at the assertion of British sovereignty, regardless of whether it was recognized by the Crown or the courts. It burdened and continues to burden lands over which fee simple grants are issued.[19]

- Accepting that “Aboriginal title should be defined with reference to third party interests in land, such that Aboriginal title is displaced by those interests… would lead to an absurd result where Aboriginal rights would be defined by limitations arising from the Crown’s improper conduct prior to a declaration, undermining the purpose of s. 35 which protects Aboriginal title and constrains the Crown’s conduct with respect to same”.[20]

Notably, the Land Title Act does not prevent Aboriginal title holders from challenging the validity of fee simple grants. The Torrens system (which underlies the Land Title Act) intends to create security of title through registered title. The idea is that once properly registered, the interest in land is “indefeasible”. But Aboriginal title “lies beyond” the Torrens system and the Land Title Act.[21] The Land Title Act deals with interests that derive from Crown title. In contrast, Aboriginal title is an “inherent right” that arises from Indigenous peoples’ historic occupation of lands.[22]

Further, provincial legislation that prevents an Aboriginal title holder from seeking a declaration or other relief in relation to lands held in fee simple would either amount to extinguishment (which provinces are not permitted to do), or an unjustified infringement (as it denies Aboriginal title holders from exercising any of the incidents of title).

3. The exercise of Aboriginal title and fee simple rights requires reconciliation on a case by case basis

The above principles confirm that Aboriginal title and fee simple title, as a matter of law, can co-exist on the same parcel of land. There is no automatic conflict between the two legal interests. A conflict only arises if the Aboriginal title holder wishes to exercise rights that are inconsistent with a fee simple holder’s exercise of rights. In such cases, the conflict must be reconciled, either through litigation, or ideally, negotiation between the Crown and the Aboriginal title holders.[23] Specifically, the infringement/justification framework as set out in Sparrow is the “appropriate framework through which to reconcile the third party interests in Aboriginal title land”.[24] Defences like limitations, laches, and bona fide purchaser for value may also be relevant and were all advanced in this case.

Reconciling Aboriginal title and fee simple is necessarily done on a case-by-case basis. The infringement/justification framework, as well as any potential defences, require specific facts. The ruling in the Chippewas of Saugeen is also applicable here: “There is no principled reason that a treaty-protected reserve interest [or in this case, the Aboriginal title] of a First Nation should, in every case, give way to the property interest of a private purchaser”.[25] In fact, the proper question is to assess “what remains of fee simple title after Aboriginal title is recognized in the same lands.”[26] To answer this, the court must look at the particular circumstances and determine what outcome is most consistent with reconciliation. Or, preferably, the Crown and the Aboriginal title holder will negotiate a reconciliatory resolution.[27]

As outlined below, in this case, the court ultimately found that the fee simple grants were unjustified infringements on Cowichan’s Aboriginal title. This was an important foundation for the court’s declaration that certain fee simple titles, held by Canada and Richmond, were invalid and defective.

4. Fee simple grants are considered under the justified infringement framework

Fee simple grants are an infringement

The Crown argued that the infringement and justification analysis from Sparrow does not apply to historical, pre-1982 interferences.[28] The judge rejected this position, instead finding that she had to determine whether the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title was historically interfered with using the Sparrow framework.[29]

The duties that the Crown owed to Aboriginal rights and title holders has changed over time. The duty on the Crown to justify an infringement, for instance, only arose in 1982.[30] As such, the infringement analysis will depend in part on when the Crown conduct at issue occurred, and whether the impact of that conduct is continuing.[31]

British Columbia argued that the Crown grants of fee simple land were discrete historical acts that did not amount to ongoing Crown conduct such that the Sparrow analysis applies.[32] The judge rejected this argument, holding that the infringement analysis contemplates the consequences of the exercise of Crown power. Here, the consequences flowing from the issuance of the Crown grants were severe and persisted to present day. Relying on Tsilhqot’in, the judge held:

The Crown grants were a direct transfer of the Cowichan’s property rights to third parties in the form of fee simple interests. This transfer is a denial of all the Cowichan’s rights associated with their land. I can think of no more harmful conduct, no more significant intrusion, than selling Aboriginal title land to third parties without first consulting with the Indigenous people who live there, and without obtaining their consent.[33]

The judge considered the Crown grants under the Sparrow framework, finding that all three factors were made out:

- the Crown grants of fee simple interest alienated the Cowichan’s lands to third parties, which is an unreasonable limit on the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title;

- the hardship which resulted to the title holders was undue and enduring; and

- finally, there was no recognition of the Cowichan’s ownership of the land, and their ability to exercise any rights associated with their Aboriginal title (let alone their preferred means) was lost for well over one hundred years.[34]

The Crown grants of fee simple interests therefore adversely interfered with – and continue to interfere with – the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title and are a prima facie infringement.[35]

The infringement must be justified

The Crown argued that the justification analysis does not apply to actions occurring prior to 1982 and prior to a declaration of Aboriginal title.[36] The judge accepted that because s. 35 did not come into force until that date, the Crown’s duty to to justify infringements is inapplicable to discrete Crown conduct that occurred prior to 1982.[37]

However, the Crown’s duty to justify infringements applies to Crown conduct that began prior to 1982 where there is continuing interference with the Aboriginal right at the time the Aboriginal right is recognized, and so the Sparrow framework applies to pre-declaration conduct.[38] The standards required to justify an infringement under the Sparrow framework can be adjusted to the historical context.[39]

In considering whether a historic act with ongoing impacts might be justified, the analysis must consider the duties of the Crown at the time of the act – in this case when the Crown grants were issued – as well as the duties of the Crown following court recognition of Aboriginal title.[40] Where an infringement occurs prior to proof of a right, whether the Crown complied with the duties that it owed at the time the infringement occurred is relevant to whether the Crown can justify the infringement.[41] For instance, at the time of the Crown grants, BC owed the Cowichan a duty to consult which it breached. Now that the Aboriginal title of the Cowichan has been recognized, BC must meet all the elements of the Sparrow test.

At the time of the Crown grants, the power BC had over provincial land pursuant to the Constitution Act, 1867 was constrained by the Crown’s duty to consult arising from the honour of the Crown at the assertion of sovereignty.[42] The duty to consult was then triggered when BC contemplated issuing the grants, and it was breached when BC issued the grants without consulting the Cowichan.[43]

The defendants argued that the duty to consult was unknown at the time of the grants, and the court should not apply modern standards to historical acts.[44] The court rejected this argument, noting that the entire Indian reserve creation policy in BC was premised on consultation with Indigenous peoples so that colonial officials might know which lands to protect from settlement.[45] On the facts of this case, the court found that “colonial officials participated in or otherwise turned a blind eye to blatant land speculation in the entire Cowichan Title Lands which were granted to absentee owners.”[46] By the standards of the day and by any measure, BC breached the duty it owed the Cowichan in granting the lands.[47]

Now that title is established, BC must meet all the elements of the justification test set out in Tsilhqot’in: 1) that it discharged its procedural duty to consult and accommodate; 2) that its actions were backed by a compelling and substantial objective; and 3) that the action is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary obligation to the group.[48] The court rejected BC’s argument that the Crown had no further role in the infringement once the grants were made; the alienation is continuing, so BC must now re-evaluate its conduct in light of the declaration of Aboriginal title.[49] Because BC’s infringement of the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title is ongoing, BC must demonstrate that the Crown grants are backed by a compelling and substantial objective and are consistent with its fiduciary duty.[50]

The court accepted that the settlement and economic development of the Province was generally a compelling and substantial objective.[51] However, BC did not establish that the specific Crown grants at issue furthered the settlement and, in fact, the evidence demonstrated the opposite; the lands were purchased by absentee settlers and speculators.[52]

The court also accepted that the endurance of fee simple title, and private property ownership generally, was a compelling and substantial objective.[53]

However, the judge concluded that, because the grants of fee simple exclude the Cowichan from their land while granting conflicting rights to others to occupy and use the land exclusively, the grants run afoul of the principle that infringements of Aboriginal title cannot be justified where future generations are deprived of the benefit of the land.[54] The Crown grants are therefore an infringement that cannot be justified. It was unnecessary for the judge to consider the proportionality stage of the fiduciary duty analysis.[55]

It is noteworthy that, given this conclusion, it is difficult to imagine any grants of fee simple interests on Aboriginal title land ever being justified infringements.

5. Equitable defences are relevant but not made out

The court accepted that the municipality of Richmond could advance the equitable defences of laches and bona fide purchaser for value. However, the court reasoned that the defences should not be considered strictly; rather, in balancing interests, the principle of reconciliation should guide the court’s exercise of discretion to apply equitable defences.[56]

However, the evidence suggested that Richmond received the fee simple titles in tax sales for only nominal value that did not reflect the value of the land.[57] As a result, Richmond was not a bona fide purchaser for value.[58] Had Richmond paid valuable consideration for the land, the judge would have concluded that Richmond did not have prior notice, actual or constructive, of the Cowichan interest in the land, and so would have been able to make out the defence.[59] Nevertheless, even if Richmond had been able to make out the bona fide purchaser for value defence, the defence is not absolute; the court must still weigh equities to determine who, at the end of the day, should possess the land.[60]

With respect to laches, the judge readily concluded that the Cowichan did not acquiesce to the Crown grants.[61] Further, colonial disruption created enormous barriers to the Cowichan pursuing their claim.[62] Finally, Richmond had done little in reliance on the delay; the lands were mostly undeveloped, unoccupied, and unimproved.[63] Richmond was therefore unable to make out the defence of laches.

6. Conclusion

This decision is an extraordinary victory for Cowichan, and proves that even where the Crown has allowed Aboriginal title land to be improperly sold as fee simple land, that does not end the right: Aboriginal title survives, and land can be returned. This is a step forward for First Nations across the country and puts to rest once and for all the argument that where there is fee simple title there cannot also be Aboriginal title.

That said, the time spent on this claim is also extraordinary. This matter was in trial starting in September 2019, and spent 513 days in trial. Eighty-six lawyers appeared in court and 2,858 exhibits were introduced. The cost to Cowichan, both in money and in the toll it must have taken on the community to have their claim before the court for so long, must have been enormous. It is a credit to Cowichan’s perseverance for enduring this fight and prevailing.

Not all First Nations will have the resources and ability to do this. And, realistically, courts are not equipped to have numerous trials of this nature ongoing at the same time. This simply cannot be the path to achieving reconciliation and recognizing constitutionally protected rights.

As courts have repeatedly pointed out, reconciliation is ideally achieved between the Crown and Indigenous groups. It is past time that the Crown and, in its absence, courts, take steps to ensure First Nations can bring these claims in a way that is manageable and expeditious, so they don’t have to wait decades to have confirmation of rights they have always known they have.

[1] Cowichan Tribes v Canada (Attorney General), 2025 BCSC 1490 [the “Decision”].

[2] This is a first for an Aboriginal title claim in Canada although we note that fee simple title has been returned where land was declared reserve land. In Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation v. Town of South Bruce Peninsula et al., 2023 ONSC 2056, affirmed on this issue 2024 ONCA 884, the Court returned fee simple land to the claimant First Nation that had been explicitly set aside as reserve land in Treaty 72. An application for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada brought by several of the fee simple holders was dismissed with costs ([2025] SCCA No 43). The Aboriginal interest in Aboriginal title land has been held to be the same as the interest in reserve land: Guerin v. The Queen, 1984] 2 SCR 335, at 379.

[3] The exception was related to an airport fuel depot on 12 acres of Canada’s fee simple lands. The Cowichan had previously entered into an accommodation agreement related to this infrastructure and did not oppose the project: see para 42.

[4] Decision, at para 3581.

[5] Decision, at paras 3637-38.

[6] Decision, at para 3588.

[7] Decision, at para 3588.

[8] Decision, at para 3588.

[9] Decision, at paras 3584, 3586.

[10] Decision, at para 3590, citing Wolastoqey Nations v. New Brunswick and Canada, et.al., 2024 NBKB 203, at para 171. See also paras 2163 and 2208 of the Decision.

[11] Decision, at para 3588.

[12] Decision, at para 180.

[13] Decision, at para 2113.

[15] Decision, at para 2113.

[16] Decision, at para 2139.

[17] Decision, at para 2182.

[18] Decision, at para 2193.

[19] Decision, at para 2188.

[20] Decision, at para 2202.

[21] Decision, at para 2259.

[22] Decision, at para 2252.

[23] Decision, at para 2208.

[24] Decision, at para 2202.

[25] Decision, at para 2181, citing Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation v. South Bruce Peninsula (Town), 2024 ONCA 884, at para 241.

[26] Decision, at para. 2193.

[27] Decision, at para 3590.

[28] Decision, at para 2279.

[29] Decision, at para 2301.

[30] Decision, at paras 2296, 2298.

[31] Decision, at para 2296.

[32] Decision, at paras 2329, 2331.

[33] Decision, at para 2330, emphasis added.

[34] Decision, at para 2335.

[35] Decision, at para 2339.

[36] Decision, at paras 2529, 2532.

[37] Decision, at para 2566.

[38] Decision, at para 2566.

[39] Decision, at para 2566.

[40] Decision, at para 2567.

[41] Decision, at para 2591.

[42] Decision, at para 2592.

[43] Decision, at paras 2592, 2594.

[44] Decision, at para 2595.

[45] Decision, at paras 2596-98.

[46] Decision, at para 2599.

[47] Decision, at para 2604.

[48] Decision, at paras 2615, 2647.

[49] Decision, at paras 2616, 2619, 2623, 2624.

[50] Decision, at para 2648.

[51] Decision, at para 2649.

[52] Decision, at paras 2653-5.

[53] Decision, at paras 2656-7.

[54] Decision, at para 2658.

[55] Decision, at para 2659.

[56] Decision, at para 3084.

[57] Decision, at para 3103.

[58] Decision, at para 3105.

[59] Decision, at para 3111-2.

[60] Decision, at para 3632-3.

[61] Decision, at para 3118-27.

[62] Decision, at para 3140.

[63] Decision, at para 3147, 3149.

Related Posts

Aboriginal title can be declared over privately-owned land

Friday, November 15, 2024

The six Wolastoqey Nations in New Brunswick recently received a precedent-setting decision in their Aboriginal title claim. In Wolastoqey Nations v New Brunswick…

Read More...

Historic Agreement Recognizes Haida Title to Haida Gwaii

Friday, April 19, 2024

On April 14, 2024, the Haida Nation and the Province of British Columbia signed the Gaayhllxid/Gíihlagalgang “Rising Tide” Haida Title Lands Agreement. This Agreement recognizes…

Read More...

The Wolastoqey Chiefs respond to today’s NBCA decision

Thursday, December 11, 2025

Please see below the response of the Wolastoqey Chiefs to today’s New Brunswick Court of Appeal decision related to their Aboriginal title claim.

Link: